Bio

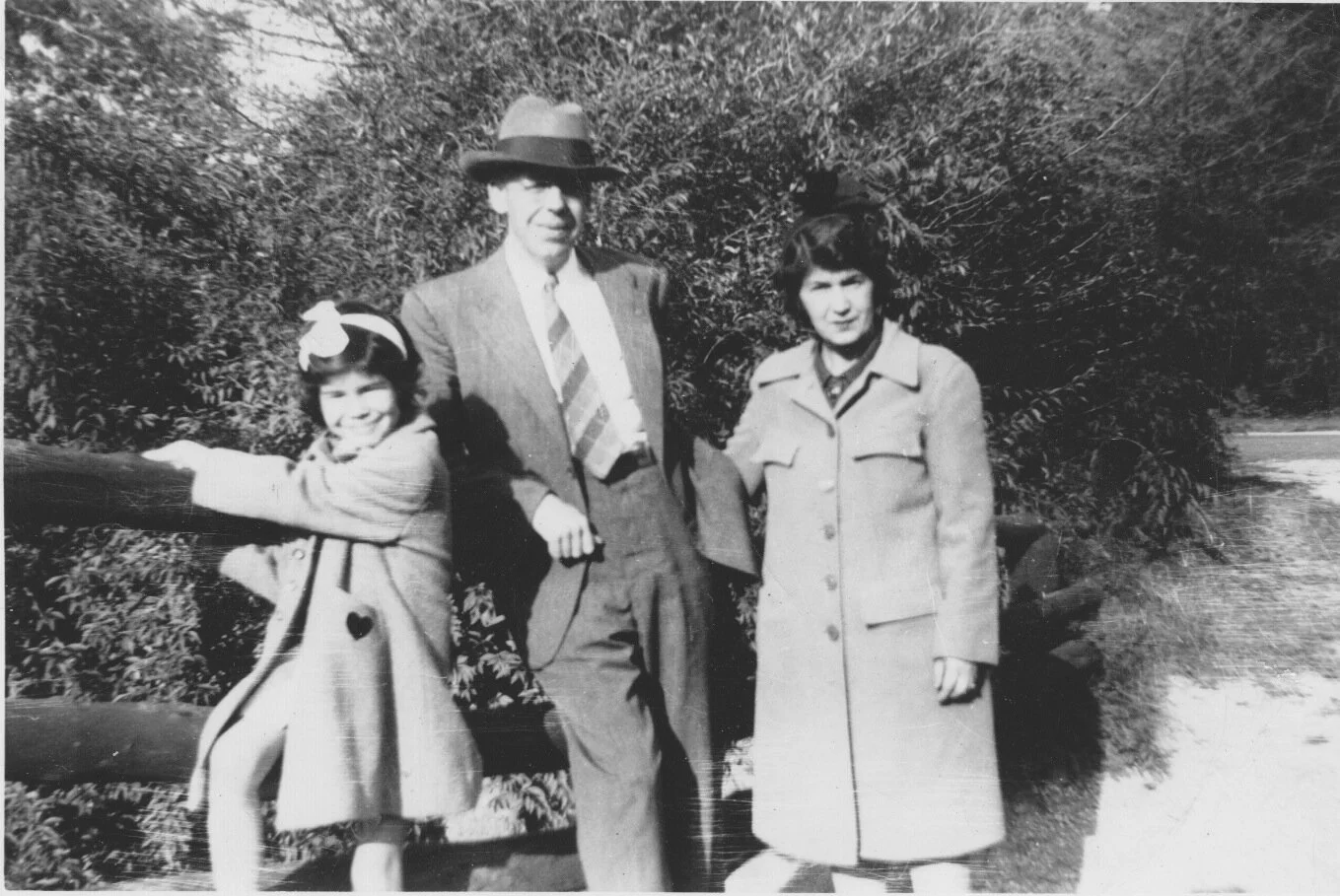

Marge Piercy was born March 31, 1936 in Detroit into a family that had been, like many others, affected by the Depression. Her mother, Bert Bernice Bunnin, born in Philadelphia, had lived also in Pittsburgh and Cleveland; her father Robert Douglas Piercy grew up in a small town in the soft coal mining region of Pennsylvania. They had not been living in Detroit long. Her father, out of work for some time, got a job installing and repairing heavy machinery at Westinghouse. When Piercy was little, they moved into a small house in a working-class neighborhood in Detroit which was black and white by blocks.

Piercy had one brother, fourteen years older, her mother’s son by a previous marriage.. Piercy’s maternal grandfather Morris was a union organizer murdered while organizing bakery workers. Her maternal grandmother, Hannah, of whom Piercy was particularly fond, was born in a Lithuanian stetl, the daughter of a rabbi. “Grandmother Hannah was a great storyteller. She and my mother told many of the same stories, but always the stories came out differently.” It was her maternal grandmother who gave Piercy her Hebrew name, Marah. Although Piercy’s father was not a Jew (he was raised a Presbyterian but observed no religion), she was raised a Jew by her grandmother and her mother and has remained one.

Piercy credits her mother with making her a poet. Piercy describes her mother as an emotional, imaginative woman full of odd lore and superstitions. She read voraciously and encouraged her daughter to do the same. Enormously curious , she urged her daughter to observe sharply and remember what she observed. As Piercy grew older and became more independent, they fought viciously. Finally, Piercy left home at seventeen and recalls that she and her mother were not really in sustained harmony until very late in her mother’s life. Her mother died in 1981. Piercy was much closer to her mother than to her father, who died in 1985.

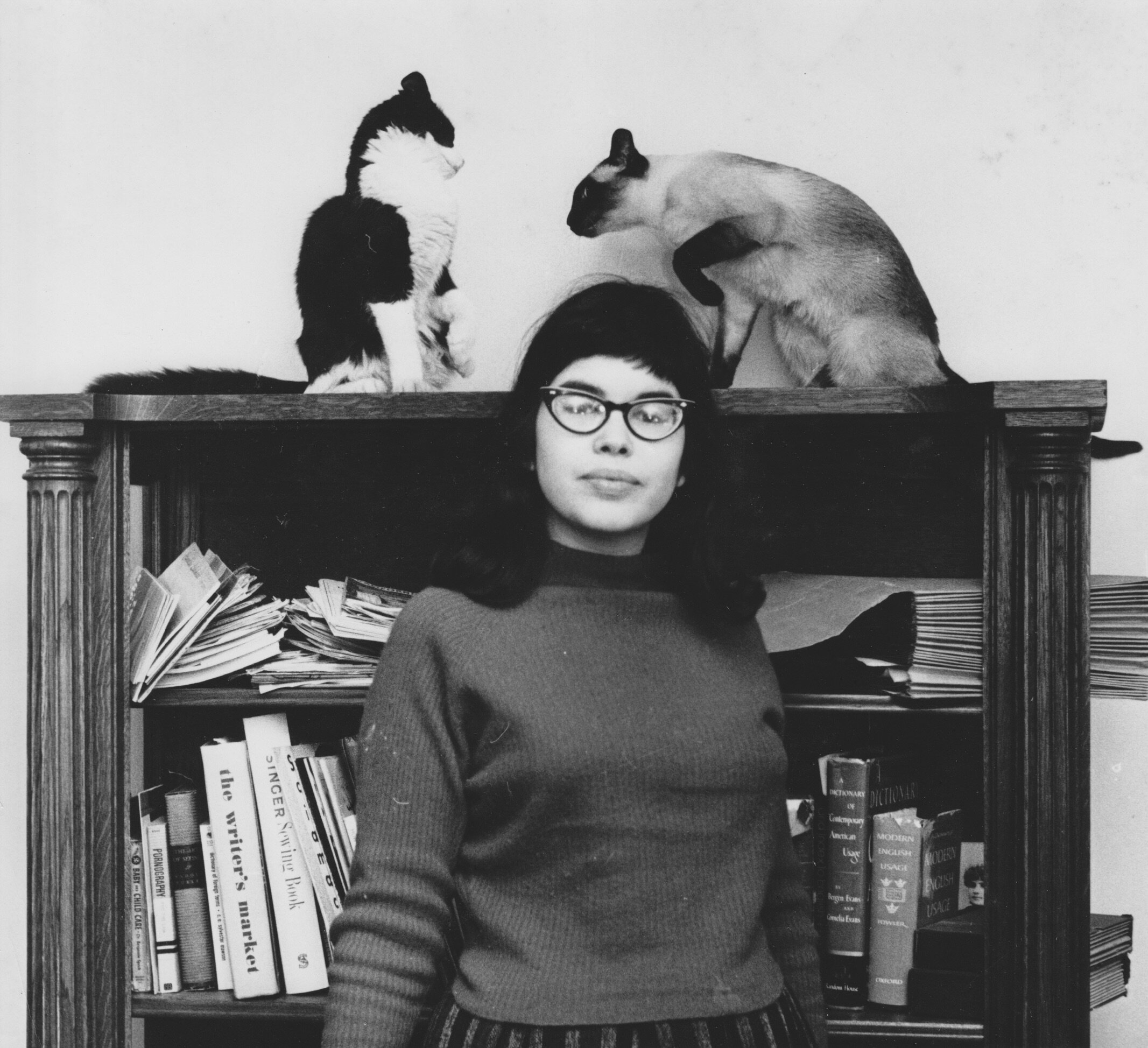

Piercy recalls having a reasonably happy early childhood. However, halfway through grade school she almost died from the German measles and then caught rheumatic fever. She went from a pretty and healthy child into a skeletal creature with blue skin given to fainting. In the misery of sickness, she took refuge in books. She lavished love on her cats. She went to public grade school and high school in Detroit. At seventeen, after winning a scholarship to the University of Michigan which paid her tuition, Piercy was the first person in her family to go to college. Piercy remarks that in some ways college was easy for her. She was good at taking exams and strongly motivated to learn. However other aspects of college life were painful.

She did not fit any image of what women were supposed to be like. The Freudianism that permeated educated values in the fifties labeled her aberrant for her sexuality and ambitions. However, winning various Hopwood awards (the playwright Avery Hopwood, writer of sex farces, had left his fortune to the University of Michigan to be used to encourage good and original student writing) meant that during her senior year Piercy didn’t have to work to support herself. A Hopwood also allowed her to go to France after graduation. Her schooling finished with an M.A. from Northwestern where she had a fellowship.

Piercy went to France with her first husband, a French Jew who was a particle physicist and who had been active in opposing the war in Algeria. Although he was a kind and bright man, his expectations of conventional sex roles in marriage and his inability to take her writing seriously caused her to leave him. Afterward, once again Piercy was extremely poor.

After that marriage, Piercy lived in Chicago, trying to learn to write the kind of poetry and fiction she imagined but could not yet produce. She supported herself at a variety of part-time jobs; she was a secretary, a switchboard operator, a clerk in a department store, an artists’ model, a poorly paid part-time faculty instructor. She was involved in the civil rights movement.

She remembers those years in Chicago as the hardest of her adult life. She felt she was invisible. As a woman, society defined her as a failure: a divorcee at twenty-three, poor, living on part-time work. As a writer, she was entirely invisible. She wrote novel after novel but could not get published. Piercy remarks that at that time she knew two things about her fiction: she wanted to write fiction with a political dimension (Simone de Beauvoir was her model) and she wanted to write about women she could recognize, working class people who were not as simple as they were supposed to be.

In 1962, she married again to a computer scientist. This second marriage wasn’t conventional and in many ways wasn’t a marriage at all. It was an open relationship and often other people lived with them. They had serious involvements that were sometimes beautiful and rich and sometimes ghastly and bumpy. They first lived in Cambridge, then in San Francisco. Eventually, they returned to the East coast and lived in Boston. At that time they were both becoming upset about the war in Vietnam. Piercy began going back and forth to Ann Arbor frequently as it was there that The VOICE chapter had been started. It was the beginning of SDS. Meanwhile, Piercy was still trying to get published. Realizing that one of the problems with the novel she was trying to sell was its feminist viewpoint, she consciously decided to take on a male viewpoint character in Going Down Fast. However, from 1965 until the collapse of her health in 1969, Piercy’s main focus was political. She always continued to write but only in the time not used up by political organizing. She would go to work by six thirty and write before anyone else was stirring. After that she would begin a full day and evenings of political work. She wrote Dance the Eagle to Sleep that way.

In the spring of 1965, they moved to Brooklyn. She researched the CIA; helped found NACLA and did power structure research. She continued to be active in SDS, starting an MDS chapter in Brooklyn that was the adult off-campus SDS. In 1967, she became an organizer with the SDS regional office in New York.

Several factors pushed them out of New York. Her health was poor. The movement community which had been close and warm was split into warring factions. It had become infiltrated by violent agent provocateurs; members were wracked by a sense of futility because the war was ongoing despite the fact that we had been opposing it for eight years. Piercy was involved in the women’s movement, organizing consciousness raising groups and writing articles, but her husband was feeling alienated and bored.

In 1971 they moved to Cape Cod. They had little notion of what it would be like to live year round on the Cape, having never lived anywhere but in the center of cities. They bought land in Wellfleet and had a simple house built. Piercy began Small changes and the Tarot poems, “Laying down the tower”. Her creativity seemed suddenly liberated as she regained health and a measure of peace.

She began gardening almost immediately. She loved grubbing in the dirt; time growing fruit, vegetable, herbs and flowers was time pleasantly spent. She became active in the women’s movement on the Cape. She also began relating to Boston as The City. She has a number of good friends there she sees regularly and often she does research in Boston. Over the years that she has lived on the Cape, she has sometimes been politically centered in Boston and sometimes on the Cape, depending on which issues she has been involved in. While Piercy quickly put down roots at the cape, he felt isolated. The relationship was really over by 1976 but disentangling emotionally and officially took years.

Piercy’s poetry has changed since moving to the Cape. She now has a sense of herself as part of the landscape and part of the web of living beings. The Cape is her home although she travels a great deal here and abroad, giving readings, workshops and lectures.

Piercy knew her current husband, Ira Wood, for six years before they married in 1982. Early on, they wrote a play together The Last White Class. He had written a number of other plays and has published two novels. They have a very close and intimate relationship. They wrote a novel together to be published in 1998, Storm Tide, and in 1997 founded the Leapfrog Press, a small literary publishing company.

She finds it important to like the routine of daily life in order to survive as a political writer in the long haul. In the past, when she did not have support at home, she has felt as if she were fighting on all fronts at once with no base. One gift Wood has given her is that warm place of support. She is a writer who feels guilty if she is not writing or writing enough. In the last fifteen years, she has become involved in Jewish renewal. She helped found the havurah of the Outer Cape, Am ha-Yam. She worked on the Or Chadash siddur and often teaches at the Jewish renewal retreat center, Elat Chayyim.

Piercy has always celebrated whatever she could find to celebrate. Her mother’s family taught her early in life to enjoy what you could because trouble is never far. Pay sharp attention to that trouble looming but don’t let it taint your Shabbat celebration. In her poetry, she bears thanks to what she has been given as well as bearing witness to what is withheld from us and what is taken away. Piercy doesn’t understand writers who complain about writing, not because it is easy for her but because it is so absorbing that she can imagine nothing more consuming and exciting at which to labor. So long as she can make her living at writing, she will consider herself lucky.

Compiled by Terry McManus